Ardain Isma

CSMS Magazine

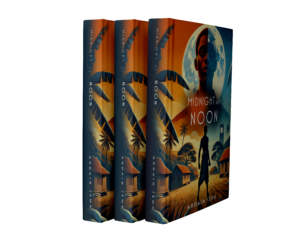

In the past year, I conducted research on the pivotal role that creole languages play in Caribbean literature, exploring their significance in preserving cultural identity and challenging linguistic hierarchies. This exploration emerged from my reflections on “Midnight at Noon,” my second published novel. In this work, I intricately weave Haitian Creole into the narrative, drawing inspiration from the positive feedback I received from non-Creolophone readers. Now, I am eager to share my thoughts with you.

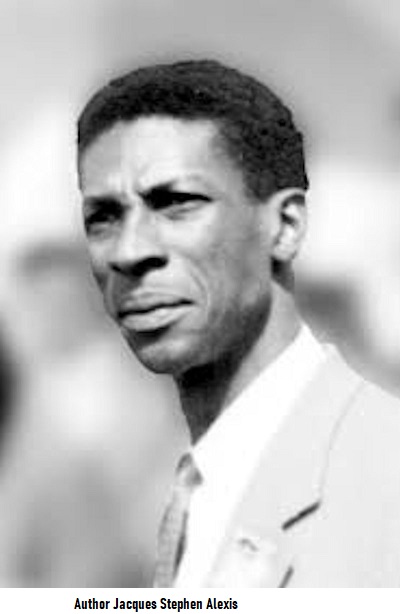

I have to say creole languages in Caribbean literature have long served as vessels of cultural heritage, offering unique perspectives and voices that break away from dominant languages. Writers who embrace these creole languages wield them as tools of resistance, asserting their authenticity and reclaiming narratives long suppressed by colonial impositions. Jacques Stéphen Alexis’ works, one of the most brilliant writers in contemporary literature in the Caribbean, confirm this assertion. His novel, “Compère Général Soleil”, is a great example.

The Caribbean, a region marked by a history of colonization and slavery, boasts a linguistic landscape rich in creole languages—complex blends of indigenous, African, and European languages. These creoles emerged as a result of the diverse cultural interactions among the inhabitants, serving as a symbol of resilience against the erasure of indigenous cultures and languages during the colonial era.

In literature, I found that these creole languages are a vital medium through which writers express the nuances of Caribbean identity. Authors like Derek Walcott, known for works like “Omeros,” skillfully weave creole languages into their writing, infusing their narratives with the rhythm and cadence of local speech. This linguistic choice allows them to capture the essence of Caribbean life, depicting the everyday struggles, joys, and complexities of the region’s people.

The significance of creole languages in Caribbean literature lies in their ability to challenge linguistic hierarchies. Historically, European languages like English, French, and Spanish were elevated above creole languages, positioning them as superior and relegating creoles to a lower status. However, writers embracing creole languages subvert this hierarchy, asserting the value and legitimacy of these languages in literary expression. Through their works, they dismantle the notion that only dominant languages are suitable for high art, carving a space for creole languages in the literary canon.

The use of creole languages in literature serves as a powerful assertion of cultural identity. It provides a platform for Caribbean writers to reclaim their heritage and assert their distinctiveness. Authors such as Jean Rhys, in her novel “Wide Sargasso Sea,” use creole languages to depict the complexities of identity and the struggle of marginalized voices, offering an alternative perspective to the dominant narratives imposed by colonial powers.

Moreover, creole languages enable writers to reach a broader audience, transcending linguistic barriers. By incorporating these languages into their writing, authors create a sense of inclusivity, inviting readers from diverse backgrounds to engage with narratives that reflect the multifaceted nature of Caribbean societies.

However, I must say that the use of creole languages in literature also faces challenges. Some critics argue that the incorporation of creoles makes texts less accessible to readers unfamiliar with these languages. This debate highlights the tension between preserving authenticity and ensuring wider comprehension. To circumvent these criticisms as well as to address the problem, many writers, out of respect for their wider audience, have included a glossary of foreign words at the end of the story.

Nevertheless, the significance of creole languages in Caribbean literature remains undeniable. They serve as a vehicle for cultural preservation, enabling writers to celebrate their heritage, challenge linguistic hegemony, and offer a more nuanced portrayal of Caribbean identities. Through the works of writers who boldly embrace creole languages, the literary landscape becomes a testament to the resilience and diversity of Caribbean cultures.

Note: Ardain Isma is the Chief-Editor of CSMS Magazine. He is the author of several books, including Midnight at Noon, Bittersweet Memories of Last Spring, and Last Spring was Bittersweet. You can order these books by clicking on the links above.